Artas, Bethlehem

Artas | |

|---|---|

| Arabic transcription(s) | |

| • Arabic | أرطاس |

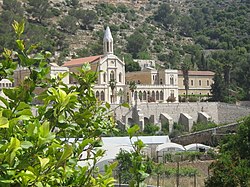

Artas, Convent of the Hortus Conclusus | |

Location of Artas within Palestine | |

| Coordinates: 31°41′21″N 35°11′10″E / 31.68917°N 35.18611°E | |

| Palestine grid | 167/121 |

| State | State of Palestine |

| Governorate | Bethlehem |

| Government | |

| • Type | Village council |

| • Head of Municipality | Hamdi Aish |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4,304 dunams (4.3 km2 or 1.7 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 732 m (2,402 ft) |

| Population (2017)[2] | |

| • Total | 5,745 |

| • Density | 1,300/km2 (3,500/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | Urtas, p.n.[3] |

Artas (Arabic: أرطاس) is a Palestinian village located four kilometers southwest of Bethlehem in the Bethlehem Governorate of Palestine, in the central West Bank. According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, the town had a population of 5,745 in 2017.[4]

Etymology

[edit]According to le Strange, the name Urtas is probably a corruption of Hortus, which has the same meaning as Firdus (Paradise),[5] while E.H. Palmer thought it was a personal name.[3] The name might also be derived from Latin hortus meaning garden, hence the name Hortus Conclusus of the nearby Catholic Convent.

Geography

[edit]Artas is located 2.4 kilometers (1.5 mi) (horizontal distance) southwest of Bethlehem. It is bordered by Hindaza to the east, Ad Duheisha camp to the north, Al-Khader to the west, and Wadi Rahhal to the south.[1] The Israeli settlement of Efrat is located nearby.

Artas and the surrounding area is characterized by the diversity of landscapes, flora and fauna due to its location at a meeting place of ecosystems.[6] From a spring below the village an aqueduct used to carry water to Birket el Hummam. [7]

History

[edit]Fatimid to Mamluk eras

[edit]According to Moshe Sharon, professor of early Islamic history at Hebrew University, two inscriptions found in the village show the great interest in Artas from leaders in the Fatimid and Mamluk states, as well as the wealth of the village at that time.[8]

Nasir Khusraw (1004–1088) wrote that "a couple of leagues from Jerusalem is a place where there are four villages, and there is here a spring of water, with numerous gardens and orchards, and it is called Faradis (or the Paradises), on account of the beauty of the spot."[5]

During the Crusader period, the village was known as Artasium, or Iardium Aschas. In 1227, Pope Gregory IX confirmed that the village had been given to the Church of Bethlehem.[9] Remains of the Crusader church were torn down in the 19th century.[10]

Ottoman era

[edit]

Artas was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 1517 with all of Palestine, and in 1596 it appeared in the tax registers as being in the Nahiya of Quds of the Liwa of Quds. It had a population of 32 Muslim households. The villagers paid a fixed amount of 5,500 akçe in taxes, and all of the revenue went to a Muslim charitable endowment.[11]

The village was reportedly destroyed twice during the Ottoman period: first, between 1600 and 1744, and again in the late 18th century.[12]

Until the 19th century, Artas residents were responsible for guarding Solomon's Pools, a water system conducting water to Bethlehem, Herodium, and the Temple Mount or Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem. The village had a tradition of hosting foreign and local scholars, not a few of whom were women.[13] A large body of research thus exists on many aspects of life in the village.[14]

The residents of Artas refused to pay tributes to Ibrahim Pasha in 1831 under the pretext that they had been exempt since the time of Solomon. He responded by demolishing their homes, which they later rebuilt[15]

In 1838, Robinson and Smith described Artas as a Sunni Muslim village south of Wadi er-Rahib.[16] The place was inhabited but many houses lay in ruins. Robinson also found many signs of antiquity, including foundations of a square tower.[17] He further noted the fine fountain above it, which watered many gardens.[18]

In the mid-19th century, James Finn, the British Consul of Jerusalem (1846–1863),[19] and his wife Elisabeth Ann Finn, bought land in Artas to establish an experimental farm where they planned to employ poverty-stricken Jews from the Old City of Jerusalem. Johann Adolf Großsteinbeck (1828–1913; grandfather of the author John Steinbeck) and his brother Friedrich, settled there under the leadership of John Meshullam, a converted Jew and member of a British missionary society.[20] Clorinda S. Minor also lived in Artas in 1851 and 1853.

When the French explorer Victor Guérin visited in July 1863,[21] he found 300 inhabitants. Many of the houses appeared to be built of ancient materials.[22] An official Ottoman village list from about 1870 showed 18 houses and a population of 60, though the population count included only men.[23][24]

In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described Artas as "a small village perched against hill-side...with a good spring behind it whence an aqueduct led to Jebel Furedis...remains of a reservoir Humman Suleiman."[25]

In 1896 the population of Artas was estimated to be about 120 persons.[26]

British Mandate era

[edit]

According to German explorer and orientalist Gustaf Dalman, in the early 20th-century, Artas supplied the Jerusalem marketplace with peaches, apricots and green pears.[27]

The Finnish anthropologist Hilma Granqvist came to Artas in the 1920s as part of her research on the women of the Old Testament. She "arrived in Palestine in order to find the Jewish ancestors of Scripture. What she found instead was a Palestinian people with a distinct culture and way of life. She therefore changed the focus of her research to a full investigation of the customs, habits and ways of thinking of the people of that village. Granqvist ended up staying till 1931 documenting all aspects of village life. In so doing she took hundreds of photographs."[28] Her many books about Artas were published between 1931 and 1965, making Artas one of the best documented Palestinian villages.

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, "Urtas" had a population of 433, 192 male and 197 female Muslims, and 1 male and 43 female Christians.[29] In the 1931 census the population of Artas was a total of 619 in 123 inhabited houses. There were 272 male and 273 female Muslims, while there was 5 male and 69 female Christians.[30]

In 1944, archaeologist Grace M.Crowfoot, while researching Palestinian weaving techniques, recorded two lullabies being sung in Artas:[31]

O pigeon of the rivers,

Give sleep to both eyes.

O pigeon of the wilderness,

Give sleep in the cradle.

O pigeon of the valley,

Give sleep to my son.

O bird, O pigeon,

My darling wants to sleep.

And I'll slay the pigeon for thee,

O pigeon, do not fear,

I'll but laugh the child to sleep.

In the 1945 statistics the population of Artas was 800; 690 Muslims and 110 Christians,[32] who owned 4,304 dunams of land according to an official land and population survey.[33] Of this, 894 dunams were plantations and irrigable land, 644 for cereals,[34] while 54 dunams were built-up (urban) land.[35]

Jordanian era

[edit]In the wake of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, and after the 1949 Armistice Agreements, Artas came under Jordanian rule. It was annexed by Jordan in 1950.

In 1961, the population of Artas was 1,016,[36] of whom 68 were Christian, the rest Muslim.[37]

Post-1967

[edit]Since the Six-Day War in 1967, the town has been under Israeli occupation. The population in the 1967 census conducted by the Israeli authorities was 1,097.[38]

After the 1995 accords, 66.7% of Artas land was classified as Area C, 0.06% as Area B, the remaining 33.3% as Area A. According to ARIJ, Israel has confiscated about 421 dunams of Artas land for the Israeli settlement of Efrat.[39]

Religious institutions

[edit]Across the valley from the village is the Christian Convent of the Hortus Conclusus (lit. "Enclosed Garden", a name relating to both the Song of Songs and the Virgin Mary).[40]

Cultural institutions

[edit]The Artas Folklore Center (AFC) was established in 1993 by Mr. Musa Sanad[41] to document, preserve and share the rich heritage of the village. The village has a small folklore museum, a dabka and a drama troupe. The Artas Lettuce Festival has been an annual event since 1994. Artas is a popular destination for visitors to Bethlehem who want to experience traditional Palestinian life, and for groups interested in ecotourism.[42]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Artas Village Profile ARIJ, p. 4

- ^ "Main Indicators by Type of Locality - Population, Housing and Establishments Census 2017" (PDF). Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-01-28. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

- ^ a b Palmer, 1881, p. 330

- ^ Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (February 2018). "Preliminary Results of the Population, Housing and Establishments Census 2017" (PDF). p. 76. Retrieved May 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Le Strange, 1890, p. 440

- ^ Artas Valley[permanent dead link]

- ^ Conder & Kitchener, SWP III, 1883, p. 161

- ^ Sharon, 1997, pp. 117- 120

- ^ Röhricht, 1893, p. 259, no 983; cited in Pringle, 1993, p. 61

- ^ Baldensperger, 1913, p. 114

- ^ Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 116

- ^ Grossman, David (1986). "תהליכי התפתחות ונסיגה ביישוב הכפרי בשומרון וביהודה בתקופה העות'מאנית" [Oscillations in the Rural Settlement of Samaria and Judaea in the Ottoman Period]. מחקרי שומרון: קובץ מחקרים [Shomron Studies] (in Hebrew). Ra'anana: הקיבוץ המאוחד [Hakkibutz Hameuchad]. p. 366.

- ^ A Century and a Half of Women's Encounters in Artas[usurped]

- ^ Recommended Reading and Selected Bibliography of Artas[usurped]

- ^ Bagatti, B. (2002). Ancient Christian Villages of Judaea and Negev. Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press. p. 61.

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 3, 2nd appendix, p. 123

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 2, p. 168

- ^ Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 2, p. 164

- ^ Webster, Gillian (1985). "Elizabeth Anne Finn". The Biblical Archaeologist. 48 (3): 181–185. doi:10.2307/3209937. JSTOR 3209937. S2CID 163343573.

- ^ Friedman, Lior (4 April 2009). "The Mountain of Despair". Haaretz. Tel Aviv. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Guérin, 1869, p. 104 ff

- ^ Guérin, 1869, p. 108

- ^ Socin, 1879, p. 144 It was noted in the Hebron district

- ^ Hartmann, 1883, p. 148

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1883, SWP III, 'Urtas'. p. 27.

- ^ Schick, 1896, p. 125

- ^ Dalman (2013), vol. 2, pp. 388, 578

- ^ Other Palestines Archived August 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine 24–30 May 2001 Al-Ahram Weekly Online

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Bethlehem, p. 18

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 35

- ^ Crowfoot, Grace (1944). Handcrafts in Palestine: Jerusalem hammock cradles and Hebron rugs. Palestine Exploration Quarterly January–April, 1944. p. 122

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 24

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 56 Archived 2008-08-05 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in 1970, p. 101

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 151

- ^ Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics, 1964, p. 23

- ^ Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics, 1964, pp. 115-116

- ^ Perlmann, Joel (November 2011 – February 2012). "The 1967 Census of the West Bank and Gaza Strip: A Digitized Version" (PDF). Levy Economics Institute. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ^ Artas Village Profile, ARIJ, p. 17

- ^ Hortus Conclusus (the Sealed Gardens)[permanent dead link]

- ^ Musa Sanad 1949 - 2005 A Modern Day Palestinian Folk Hero Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback Machine By Leyla Zuaiter

- ^ "Welcome To Bethlehem.ps". Archived from the original on 2008-06-15. Retrieved 2008-04-22.

General references

[edit]- Baldensperger, P.J. (1913). The Immovable East: Studies of the People and Customs of Palestine. Boston.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Canaan, T. (1927). Mohammedan Saints and Sanctuaries in Palestine. London: Luzac & Co. Archived from the original on 2019-05-16. Retrieved 2015-04-09. (pp. 66 Archived 2017-10-03 at the Wayback Machine 96)

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Dalman, G. (2013). Work and Customs in Palestine. Vol. I/2. Translated by Nadia Abdulhadi Sukhtian. Ramallah: Dar Al Nasher. ISBN 9789950385-01-6. OCLC 1040774903.

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics (1964). First Census of Population and Housing. Volume I: Final Tables; General Characteristics of the Population (PDF).

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Granqvist, H, 1931: Marriage conditions in a Palestinian village I. Helsingfors: Societas Scientiarum Fennica

- Granqvist, H, 1935: Marriage conditions in a Palestinian village II. Helsingfors: Societas Scientiarum Fennica

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 3. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2012-10-18.

- Hartmann, M. (1883). "Die Ortschaftenliste des Liwa Jerusalem in dem türkischen Staatskalender für Syrien auf das Jahr 1288 der Flucht (1871)". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 6: 102–149.

- Hütteroth, W.-D.; Abdulfattah, K. (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Le Strange, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Pringle, D. (1993). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: A-K (excluding Acre and Jerusalem). Vol. I. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39036-2. .

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 2. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Vol. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Rogers, Mary Eliza (1865). Domestic life in Palestine. Poe & Hichcock.

- Röhricht, R. (1893). (RRH) Regesta regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII-MCCXCI) (in Latin). Berlin: Libraria Academica Wageriana.

- Saulcy, L.F. de (1854). Narrative of a journey round the Dead Sea, and in the Bible lands, in 1850 and 1851. Vol. 2, new edition. London: R. Bentley.

- Schick, C. (1896). "Zur Einwohnerzahl des Bezirks Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 19: 120–127.

- Sharon, M. (1997). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, A. Vol. I. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-10833-5.

- Socin, A. (1879). "Alphabetisches Verzeichniss von Ortschaften des Paschalik Jerusalem". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 2: 135–163.

- Tobler, T. (1854). Dr. Titus Toblers zwei Bucher Topographie von Jerusalem und seinen Umgebungen (in German). Vol. 2. Berlin: G. Reimer. (pp. 952- 955)

External links

[edit]- Welcome To Artas

- Artas, Welcome to Palestine

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 17: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- Artas Village (Fact Sheet), Applied Research Institute–Jerusalem (ARIJ), with aerial photo

- Satellite View of Artas

- The Palestinian Village Artas Falls in the Vortex of the Segregation Wall 21 July 2004, POICA

- Dabke Artas Lettuce Festival 2007 Part One, YouTube

- Dabke Artas Lettuce Festival 2007 Part Two, YouTube